Tomorrow morning myself, my father, and some.... other Baltimoreans will be running in October's annual Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure. It's an event in which people within my circle of family and friends have been participating since I was in middle school. In recent years it has become a tradition of sorts for my father and some combination of my sisters, our significant others, and myself to run as well. And as the granddaughter of a survivor of breast cancer, my connection to the illness is more than tenuous. But as a graduate sociology student, and in particular as a student of epidemiology, my increasing knowledge surrounding cancer acts as a small caveat to my participation in the Race for the Cure.

For the earlier part of the 20th century, the major causes of death were deseases which could be classified as infectious. Tuberculosis, pneumonia, measles, influenza. With short latency periods and high rates of mortality, infectious diseases primarily affected the young resulted in death or full recovery. Infectious diseases were curable but, to put things crudely, they also evoked a sort of natural selection whereby the more weak succumbed to disease while those who could build up some semblance of resistance made it through their childhoods. Individuals with heartier constitutions lived to their reproductive years and passed such infection-resistant traits on to their progeny while those who were unable to battle the disease passed away prior to their childbearing days. And for those who did survive, vaccines were created to suppress incidence. Thus deaths by many infectious diseases have been virtually eliminated.

Chronic diseases, on the other hand, are nearly the opposite of their infectious counterparts. Affecting a primarily older population, these illnesses are incurable with lengthy latency periods and innumerable causal factors. Cancer falls into this category as does heart disease, stroke, and diabetes among others. Since an older population is affected, there is little to no natural selection at work. The victims of chronic diseases are already beyond their reproductive years and have passed their genetic susceptibilities onto their children, who will find themselves affected most likely during their older age as well. Thus there is no natural reduction in occurrence over time. And many people can live with these illnesses for years, some even overcome them, but they are ultimately, by definition, incurable diseases. And this is what my whole Race for the Cure participation caveat rests upon.

I completely understand the desire to find a cure for cancer, a disease that nearly all of us have been affected by in one way or another, even if that be simply knowing someone who suffers from some form of cancer. But I also understand, now more than ever, that this effort will most likely be a fruitless one. I don't mean to be a pessimist or nonbeliever, but by its very definition as a chronic illness, cancer is incurable.

On the other hand, I think efforts to improve the quality of and extend the length of the lives of people with cancer are more realistic, beneficial, and efficient goals. Even better yet would be to see some true devotion to prevention of cancer and other rampant chronic illnesses. Our society places so much attention on treatment after the conception of disease when more of our focus must be devoted to prevention efforts to offset if not entirely avoid conception. There are innumerable things that we can do on both social and individual levels to make our environment, our homes, our families, and ourselves less ridden with chronic illness. Organizations like

Breast Cancer Action, about which

I posted a few months back, are turning the spotlight onto the perpetrators of our increasingly carcinogenic world. Rather than searching for a cure that may never be found, their efforts are directed at changing the world we live in so as to stem the tide of cancer-causing environmental factors.

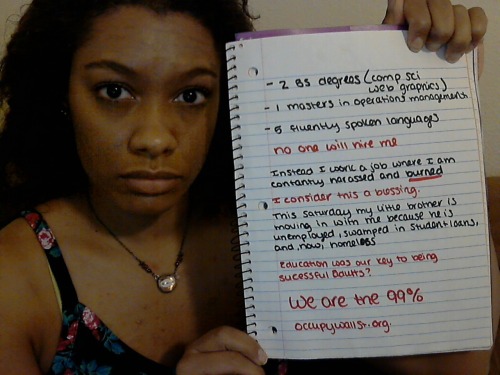

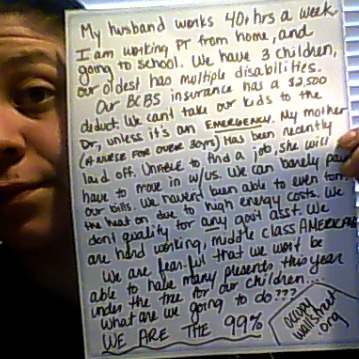

The Susan G. Komen Foundation and its Race for the Cure events are truly remarkable. They stand as testaments to the power of excellent advocacy, fundraising, issue framing, and more. But imagine how different our world would be if those eponymous pink ribbons represented (and if all their associated products funded) not the search for a cure to end breast cancer but the effort to research and develop preventative techniques and lifestyles. Or what if millions of people across the United States participated in 5k runs and walk-a-thons to fundraise for solutions to problems more achievable, such as hunger and homelessness. Social ills near and far require time and money to curtail. If these problems, including genocide, human trafficking, and starvation, were the cause behind fundraising events as popular and wide spread as the Race for Cure, think of where our world could be. Maybe it's because they simply aren't relatable to middle class Americans or maybe people don't have a proper understanding of the scope and reality of these life-or-death issues. I just can't help thinking of the multitude of dire causes that need just as much, if not more, attention as breast cancer.

Despite my various misgivings, I still enjoy participating in the Race for the Cure. Though the true aim is to find a cure for breast cancer, the event is also ripe with celebrations of womanhood, community, health, and more. Sponsors such as Panera Bread, Yoplait, and others come out in droves to support participants, provide free food (Panera's pink ribbon bagels are quite the draw for me!), and demonstrate their endorsement of the Susan G. Komen Foundation. People find unbelievably creative ways to bring pink into every last facet of their outfit while others list the names of victims of breast cancer in whose names they are running. The race is far more than 5k and this is, I believe, one of its true strengths. Though I wish this type of attention and fanfare could be redirected to more realistic and practical goals, I love to see people so rallied up about something in which they believe and for which they truly care. It gives me hope that, when messages are delivered in compelling, inspiring, and unavoidable ways, they have the capacity to do unlimited good. And it is this aspect of the Race for the Cure that keeps me running and allows me to hold out hope that the call for preventative policies and actions are not far behind the search for a cure.